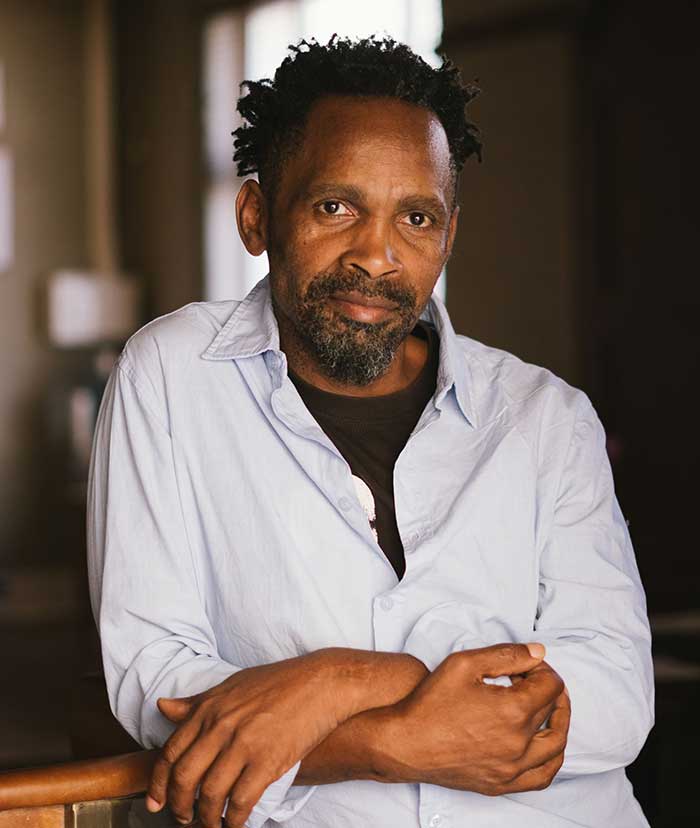

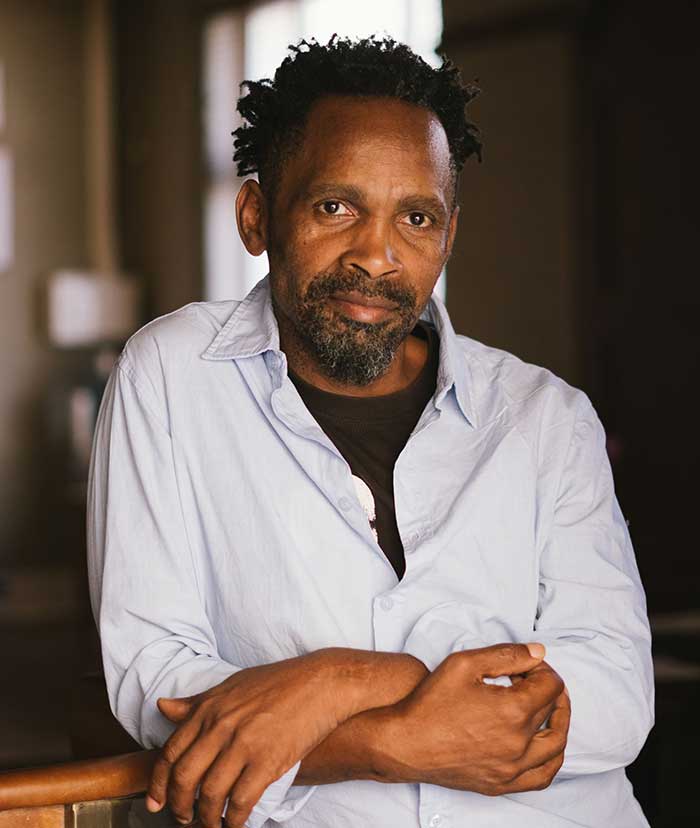

Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta (b. 1967) is a painter and poet who trained both informally (under the likes of George Pemba) and formally at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, and also completed his master’s degree in creative writing at Rhodes University in 2016.

He has held numerous solo shows in South Africa and one in the USA and participated in residencies and group exhibitions across the globe; including the USA, the Netherlands, Sweden and Nigeria. He has also served as a co-curator in the PACA (Pan African Circle of Artists) biennale in Nigeria, as a judge in South Africa’s ABSA L’atelier National Arts Competition, and as an art lecturer. He published his first collection of poems, Skeptical Erections, in 2019.

Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta’s studio is situated in the heart of his personal history – the same township neighbourhood where he was born, where he watched soccer matches as a boy, where he has lived and worked his whole life. In a nearby neighbourhood, as a young teenager, he trained under George Pemba (whom he refers to as the “grand master of township life scenes”), before studying art formally in the mid-90s via Intec College and later at the nearby Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University.

This local environment remains the source of his inspiration, but not in the way one might expect: Sapeta employs colour, form and composition to portray an emotional environment rather than the physical one. His work speaks of the alienation and degradation of existence in the impoverished urban townships of South Africa – and the societal ills that congregate around such existence. These complex and brutal circumstances are deliberately reduced, condensed or distorted – brutalised even further – by Sapeta’s expert treatment in acrylics, creating works that confront and unsettle the viewer.

Narrative is fragmented, characters and objects isolated and stripped down, threatened and overwhelmed by flat backgrounds of vivid colour. His figures are simultaneously heavy and untethered, decontextualised and anonymous – they speak of the human condition rather than the particular human, in service of the artist’s pursuit of prioritising another, abstracted identity, what he describes as “an alienated atmospheric character in my work.”

Averse to formula or stagnation, Sapeta cultivates constant change in his practice, continually exploring technical treatment of his subject, and interrogating his subject matter. 2017 saw thus a shift in his work towards a more idiosyncratic rendering of figures – even resembling portraits. Once reduced, obscured and, as Sapeta describes, “crammed into canvas corners and off the centre, [his figures] now occupy more space”, and the “subject takes centre stage”. But crucially, even in this recent work, identity is non-specific in order to foreground something more psychological and existential – something the artist achieves with several creative decisions and processes.

When choosing his models, he explains: “I look for certain faces that speak to me. Tell me a whole lot of history from a visual point of view.” He photographs the models, then returns to his preferred working environment of solitude, to paint them and “expose them in the most horrible light possible”, referencing the bleakness of survival in urban spaces. In an almost hyperreal manner, Sapeta exaggerates and emphasises certain features, at times playing on racial stereotypes – for example, exaggerating big, red lips – injecting his work with satirical edges. While his recent colour palette is more muted than in earlier work, it is still used to “suffocate” his subjects – with flat, anonymous backgrounds offering the subject “nowhere to retreat to”.

The intention of this treatment is to convey a profound duality: On one hand, the oppressive anonymity in bleak and pervasive circumstances; on the other, a sense of self-possession and ownership of plight. As the artist states, the subjects’ “permanent unacknowledged realities must be eminent.” It’s a masterful paradox of vulnerability vs. dignity, where subjects are both distorted and respected; they “own their space, they own their poverty, they interrogate you as the audience”. They return the gaze, confronting any possibility of voyeuristic power.

Facebook Dolla Sapeta